Acrophobia

You can tack “-phobia” onto almost anything in order to create a label for a fear. Some of the most common fears include: arachnophobia (fear of spiders), ophidiophobia (fear of snakes), and acrophobia (fear of heights). The study of phobias is an interesting field, and the most common fears seem to stem from the instinct to survive, which makes a lot of sense. After all, several species of spiders and snakes have deadly bites, and falling from a great height is most assuredly not the best thing for your health. Chapman University in Orange, California published a study titled America’s Top Fears of 2015, which revealed some interesting findings. In their paper, the top 3 fears were the fear of government corruption, the fear of becoming a victim of cyber-terrorism, and the fear of personal information being tracked by corporate entities. The last fear listed seems rather Orwellian, especially as you can protect your digital profile on your computer and smartphone by thoughtfully updating your privacy settings. So much for the “survival instinct” fears, right? It seems that modern man’s fears have become much more sophisticated. In any case, fear is often the response to things or conditions beyond our control, whether or not the thing in question is really harmful to us physically.

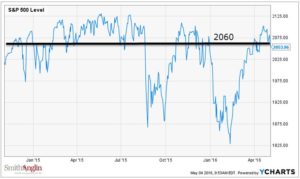

Let’s take some time to look at the stock market’s apparent fear of heights. The first time the S&P 500 broke above 2,060 was just before Thanksgiving of 2014, which was also just prior to the free-fall in oil prices. The S&P spent time at or above that 2,060 level in December 2014, and then traded above 2,060 again from February until August 2015. The chart shows a lot of volatility during this time as the S&P zig-zagged above and below the 2,060 mark during October, November, and December of 2015, before plummeting in January and February of this year, and finally pushing back above 2,060 again last month. It’s as if the stock market, as a proxy for its underlying investors, is afraid of the lofty confines of the 2060 Club. And the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA), even though it’s a representative basket of only 30 stocks, is behaving much the same way, except the bogey for the Dow has been the 18,000 point level. The Dow was less than two hundred points away from 18,000 in November 2014, and it took another month for it to finally attain that magic number. Then the Dow bounced around 18,000 for much of 2015, but seemed to fear that height and retreated by almost 2,000 points three different times, last September and again in January and February of this year. Merely eye-balling a chart of the price of these two indices and it’s obvious that we’re about where we were 18 months ago. Let that sink in for a moment. Both stock benchmarks seem to like the climb up the mountain, but then after looking around, become afraid of the view and limp back down the mountain.

Regular readers of this blog are familiar with the issues we believe are causing markets to remain range bound: earnings, central bank policies, oil’s recent amazing ride, and the economic environment. While there are many complexities and nuances influencing today’s markets, we believe these issues remain the most important.

“April is the cruelest month”

The opening line of T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” is a fitting one for this most recent earnings season. If earnings estimates and actual reports continue as expected, we’ll be looking at the first time the S&P 500 index has seen four consecutive quarters of year-over-year declines in earnings since Q4 2008 through Q3 2009. And that’s not an earnings time period you want to be tracking with, folks. At the time of this writing, 7 of 10 sectors of the economy are reporting year-over-year declines in earnings, lead by the Energy and Materials sectors. Not good. Some market prognosticators have tried to soften the blow by arguing that we’re experiencing a profit recession and not an economic recession. They suggest that the outlook for stocks is not as ugly as others might claim.

One of the bigger storylines of 2015 was how strong investment results were delivered by a small number of companies, the “FANG” stocks (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, and Google). The follow up to that story shows mixed results. Facebook and Amazon posted strong earnings and moved higher in April, with both stocks now either at or near their all-time highs. Netflix and Google are on a different trajectory, at least for now. Both posted disappointing results last month, and both closed lower in April, moving further away from all-time high prices. And it’s old news to just about everyone that the energy sector has been badly beaten down since oil’s price collapse last year. Recently, even sector heavyweight Exxon Mobil suffered a downgrade in its credit quality rating, from AAA to AA+, leaving Microsoft and Johnson & Johnson as the only two U.S. companies with the top of class AAA rating. The times they are a changin’.

Most earnings analysts don’t expect to see better earnings and revenue data until the second half of 2016. No matter how you try and paint the picture, the long-term driver of equity prices is earnings and profitability. But if that’s true, then what’s keeping stocks from trading significantly lower in light of all of the negative data?

Control

There are powerful people and institutions in this world, and you’ve seen their names many times in past newsletters: Janet Yellen and the Federal Open Markets Committee (FOMC), Mario Draghi and the European Central Bank (ECB), Shinzo Abe and the Bank of Japan (BoJ), Christine Lagarde and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the seemingly faceless People’s Bank of China (PBoC). Central bankers the world over exert massive influence on the economic environment, the conditions in which business is done. They control interest rates and the cost of borrowing. They control monetary supply and the massive balance sheets of the world’s most influential economies. And ultimately they greatly influence the subjective concept of value, specifically as it applies to the world of investing.

In April, the FOMC, ECB, BoJ, and IMF continued their pledges and policies of providing economic stimulus to their respective jurisdictions. The Fed met and put out a statement acknowledging weak global growth, but decided to refrain from making a change to the Fed Funds Rate. The ECB and BoJ left their policies in place virtually unchanged, meaning they continue pumping capital into their markets and decided to keep benchmark rates in negative territory. The PBoC pumped the equivalent of $37B into Chinese capital markets, and the PBoC has more policy tools available to use in attempting to stimulate growth.

Investing, on a basic level, is the act of buying something to participate in its profitability in light of the risk of losing your principal. There are different ways to calculate the intrinsic value of a stock, bond, or hard asset. Valuation formulas generally rely on a “risk-free rate of return”, which is usually proxied with the three-month U.S. Treasury, an instrument viewed by most as virtually risk-free. When the risk-free rate of return is 0%, for all intents and purposes, and safe investments are yielding near 0%, many otherwise conservative investors are basically forced to venture out to seek returns from riskier asset classes than they may otherwise have chosen to invest in. These investors, as new and additional buyers into the riskier asset classes, can cause the prices of those assets classes to increase, which makes the possibility of a bubble in those asset classes more likely, all other things being equal. This is one way in which stimulative monetary policies may result in “unintended consequences” – in this case a potential bubble in the value of asset classes like stocks and real estate.

A new trend for oil

Most everyone knows that the Energy sector has suffered greatly over the past 18 months, but some relief has been found in the price of oil as it has bounced back from recent lows. Oil prices started 2016 in the high $30s (US dollars / barrel), only to fall into the low $30s in January and again in February. However, since mid-February the price of oil has generally trended higher and it finished the month of April in the mid $40s. In fact, the price of oil was up about 20% in April alone. Supporting factors for higher oil prices include a weakening U.S. dollar and an oil-worker strike in Kuwait. Also, a recent meeting of OPEC and non-OPEC oil producers in Doha to discuss the state of oil production and a possible freeze in production levels failed to yield an agreement. One of the main takeaways from oil’s recent ride has been how impactful news headlines influence the day-to-day price of oil. Longer term, the problematic conditions related to too much supply will persist: daily oil production shows little sign of slowing; global oil reserves remain high; and producers haven’t displayed the unified will to cut back on production and forgo revenue now in order to send prices higher.

The fallout from lower oil prices is widespread. Slumping prices have forced many energy and energy-related companies to lay off workers. Companies have logically cut back on long term projects, a headwind for jobs growth and capital expenditure outlays. We’ve previously pointed out that one of the likely outcomes from the tumult in the energy sector will be a spike in loan defaults by cash-strapped energy companies. Many oil companies who borrowed money to finance operations are now in more trouble than they’ve ever been in before, and eventually many of these languishing players will begin defaulting on their loans. Fitch, one of the largest credit-rating agencies in the U.S., raised its 2016 forecast for U.S. high-yield bond defaults to $70billion total, of which $40billion resides in the Energy sector. According to Standard & Poors, another large credit-rating agency, the number of total corporate defaults globally this year is already up to 40, the most this early in a year since 2009. At the depths of the financial crisis, there were 67 defaults per year.

“The times they are a changing’”

For the longest time, Apple was a—probably the—darling of the tech world. The company has a formidable history of rolling out products and services that consumers around the world love: the iPod, the iPhone, the Mac, and even the iTunes store. Last month, Apple reported its first year-over-year earnings decline since 2013. Now some investors are even questioning the outlook for the company. This just goes to show you how it’s really getting tough out there … even for the big guys!

Apple’s recent rough patch serves as a good backdrop for why stocks may struggle to keep climbing. There are two opposing forces that we think will continue to prevent stocks from establishing a longer-term trend. The first force is earnings. Without healthy earnings and attractive profit margins, you’re somewhat at a loss to figure out what will serve as a catalyst for longer-term, higher stock prices. The second force is central bank policy. The world’s largest and most influential central banks have implemented quantitative easing (QE), zero interest rate policy (ZIRP), negative interest rate policy (NIRP), and there’s now increasing speculation around the possibility of “helicopter money” (yes, free money from the government, straight to you) being dispensed to the consuming public. All that central bankers have rolled out so far has been done in the spirit of “stimulating economic growth and business”, so what could possibly be more simulative to spending and consumption than putting some cold, hard cash in your hands? While some of the central banks may have seemed to pause in April, don’t ever doubt that they’ve changed their course. The stimulus probably isn’t over, not by a long shot, as central bankers share the view that tepid global growth needs their help.

And there are other forces, still, which pose risks for the marketplace. In the United Kingdom, there will be a referendum this summer which could lead to a UK exit from the European Union. Closer to home, Puerto Rico continues to create headlines with more rounds of defaulting on its debt. And the biggest headline here in the U.S has to be the unique presidential election season we’re all witnessing. To be sure, risks abound, but we believe the prudent approach to mitigating risk is consistency and discipline.